Easter in a POW Camp

It began on April 9, 1942, but he was officially captured the very next day. Thousands of American and Filipino men were transferred from the Southern end of the Bataan Penninsula and made the march northward from the vicinity of Mariveles to San Fernando, Pampanga – a distance of approximately 80 miles. The march took 8 or 9 days and later became known as the Bataan Death March.

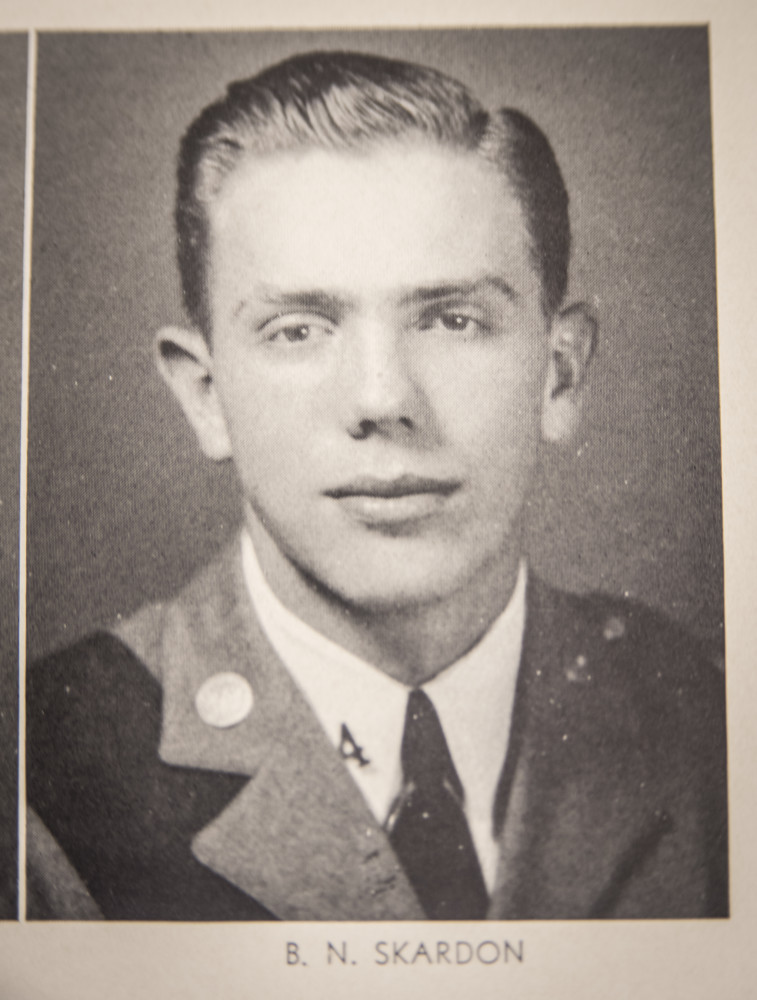

Col. Ben Skardon, Clemson University alumni and Holy Trinity, Clemson, parishioner, survived this march. Subsequently, he survived three Prisoner of War (POW) camps and two ship bombings before he was liberated by units of the Russian Army in August 1945.

Col. Skardon has endured more than most of us can fathom – and yet, he remains as humble as ever. For the past 12 years, he has travelled to the White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico to participate in the Bataan Memorial Death March.

At 102 years old, Col. Skardon is the only survivor of the actual march to participate in the memorial march. He does this, most of all, to honor Henry Leitner and Otis Morgan, the fellow Clemson alumni who took care of him when he could not take care of himself. According to Col. Skardon, in order to have a fulfilling life, you must be faithful, loyal, and have a will to live. And never forget your greatest asset.

“My greatest assets are my friends, and not what cash I might have in the bank. If I didn’t have friends, I wouldn’t have anything! I can’t imagine not having people who will listen to me or come and talk to me…”

Here is a reflection from Col. Skardon on what he calls “the most memorable of Eucharists,” on Easter Sunday, 1943.

Easter 1943

In the Spring of 1943, the Japanese Army was winning the war in Southeast Asia. For those American military personnel incarcerated in Japanese POW Camps in the Philippine Islands, the future was dreadfully uncertain. The question most privately thought or asked was “Do you think we’ll ever get out of here?”

“Here” to several thousand of us was the POW Camp near Cabanatuan, about 150 kilometers north of Manila. We worked on “the farm.” Our duties generally consisted of weeding long furrows while on our hands and knees, pulling up the weeds and grass with our fingers. Or we carried two three-gallon buckets of water for several hundred meters to irrigation ditches. Other tasks were gathering firewood for the kitchens, digging ditches, carrying stones to help build a nearby airfield, and a variety of maintenance work details. Since the tropical growing season is “year round,” the monotony and routine of these chores took a terrible toll because the constant brutality of the Japanese guards made each day on the farm a perilous and fearful experience. Each day as we left the compound, we experienced a great feeling of uncertainty-there was a doomsday atmosphere fraught with tension and dread.

Because our uniforms had become worn and tattered and since workers on the farm could not wear shoes, we were truly a bedraggled “motley crew” of American POWs. Usually, we wore a Japanese “G-string” (the equivalent of Japanese underwear), a straw hat (if you had one), and a water bottle on a piece of string or cloth, carried over your shoulder-and we were barefooted. To get back in the compound unscathed at the end of the work day was a great relief.

We were fed a serving of rice for each meal, sometimes supplemented with mongo beans, seaweed soup, or camotes. On one occasion each POW received a food box from the American Red Cross which contained a can of powdered milk, a can of salmon or corned beef, powdered coffee, a bar of chocolate, a box of raisins or prunes, and two packages of cigarettes. These boxes provided a tremendous boost for our morale.

Certain persons in our camp kept an account of the days and months of the year. “The seventh day” we all looked forward to because it was Sunday, and we did not have to work on the farm. General Protestant and Roman Catholic services were tolerated, but only at pre-approved locations and times. There was an Episcopal Chaplain in our camp; his name was Chaplain Quinn. In April of 1943, he “passed the word” that there would be a celebration of the Holy Eucharist on Easter Sunday. The service was to be very simple. We were told to “drop by” a very small nipa shack, to come singularly, to avoid attracting attention. Since this service was not approved or scheduled by the Japanese, it could have been devastating if the Japanese guards had become suspicious and had decided that something unusual was going on.

I attended this Eucharist. Chaplain Quinn had written out parts of the Communion Service plus some responses from the Book of Common Prayer (1928) on sheets of paper. The Lessons were read from a “pocket testament” which some POW had managed to keep in spite of many Japanese “shakedown inspections” and searches. The Host was made from rice which had been hand-rolled with a bottle to make flour and heated on a piece of tin to produce a wafer. The wine had been made by fermenting raisins from the Red Cross package. I do not recall what was used for the Paten, but I remember the Chalice most vividly. It was a very small ornate glass bottle, decorated with odd figures of Oriental origin. (I have often reflected on what became of our Grail.)

The small group attending the service, I’m sure, had on the “Easter Sunday best”—because it would have also been their “Monday’s best,” “Tuesday’s best,” etc. It seems bizarre now, even grotesque, to picture eight or ten skinny men variously dressed in make-shift shorts, “skivvies,” Japanese G-strings, tee shirts, clogs (hand-carved and made in camp) most with no upper clothing or shoes. Chaplain Quinn wore shoes; he was not required to work on the farm. He had on the remnants of a U. S. Army khaki uniform. However, the eye-catching item of his vesture was a very small green stole, which gave “authority” and a benediction to our gathering. He had borrowed it from the Lutheran chaplain.

Hearing the words of Communion Service after two years of privation, humiliation, and cruelty brought to mind the great community of Christian Faith. I cannot adequately express these thoughts. The magnificence and grandeur of the words of Eucharist continue to haunt my memory and my being.

Picture credits:

Picture credits:

The first black and white image, captured from the Japanese, shows American prisoners using improvised litters to carry those of their comrades who, from the lack of food or water on the march from Bataan, fell along the road. Source: National Archives and Records Administration

The two color images show Col. Ben Skardon, who has participated in the Bataan Memorial Death March 12 times. Members of the Clemson community participate in the march; this community is known as "Ben's Brigade." This year, the Rev. Suz Cate traveled to New Mexico to participate. Source: Ken Scar

The bottom image shows Ben Skardon in Army dress greens, formal photo in 1938 Clemson University TAPS yearbook.

Tags: Stories from EDUSC